About

Gary Dufour 'Some Thoughts on Sine MacPherson: Still Lifes'

STILL LIFES

STILL LIFES

Some Thoughts on Sine MacPherson: Still Lifes

Already made is a term first coined by Ellsworth Kelly in 1969. It describes a way for artists to look at and engage with the stuff of everyday life. This notion combined with the way conceptual artists question what constitutes the ‘real’ have underpinned Siné MacPherson’s painting since its inception. While much of her work may not at first glance appear to refer to reality, each is underscored by the close observation of the world.

The American artist, Ellsworth Kelly chose the word already made not out of some need for a clever play on Marcel Duchamp, but to reveal how anything can become the compositional structure for his near monochrome abstract paintings, mullions of a window, a curve in a road seen against snow, or the shadows cast across a doorway. “Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made, and it had to be exactly as it was, with nothing added. It was a new freedom; there was no longer the need to compose. The subject was there already made, and I could take from everything. It all belonged to me: ….anything goes.”1

Musée d”Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris c.1940

Ellsworth Kelly 1923-2015

Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris 1949

oil on wood and canvas

two joined panels

128.3 x 49.5 cm

Collection of the artist

© Ellsworth Kelly Estate

Joseph Kosuth (born 1945)

One and three chair 1965

wood folding chair, photograph of a chair, and photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of "chair", chair 82 x 37.8 x 53 cm, photographic panel 91.5 x 61.1 cm, text panel 61 x 76.2 cm

Museum of Modern Art New York

© Joseph Kosuth / Artists Rights Society

At around the same time, or just slightly earlier, representation was being challenged by words, objects and photography. Joseph Kosuth produced One and three chairs in 1965 .2 This work was quite simply just a chair, represented in three ways, each in combination with the others raising the question, which could be considered to be the most accurate? These three alternative representations created a new platform for exploring meaning through art.

MacPherson’s first already made was exhibited in 1979. Apron diptych is a pair of two quite similar paintings. The painting on the left is a painting of the artist’s painting apron, and the painting on the right is in fact the palette used to mix the colours used in the painting on the left, the residue of her actions mixing each colour. This work evolved into a triptych some years later when she added the original apron, folded and boxed.

Siné MacPherson

Apron Diptych 1979

oil on canvas

112 x 76 cm each

Collection of the artist

The everyday world and the overlooked guides each of us choose to navigate our path, whether that’s the Oxford Dictionary, a field guide to plants or birds, or the weather forecasts published in the daily news, all require close looking. Most, when given this close attention contain the capacity to become a compelling already made. This is the strategy at the core of MacPherson's oeuvre, ever attentive to form, colour, appearance and structure in those ordinary things around us.

Still Lifes, develop from just one such already made in a new and complex way. The series comes from a single road trip. Each shrine is from a unique moment of intense trauma and long lasting grief. The still lifes MacPherson chose to paint were already there, in many ways not unlike the reality of Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster series, commonplace catastrophes, public representations that in their ubiquity, despite our best efforts, sever the links to single individuals and particular circumstances.

In Macpherson’s Still Lifes, one can sense an underlying human compassion, but they also transcend the reality of their origins. They ask questions, similar to all of her already made paintings. Questions like when can knowing, be knowing? What changes, what do we ever know actually and what can these paintings reveal? MacPherson continually draws something to our attention, something we come across almost daily, most often in the local newspaper as front page news. However, when we are looking through the news we aren’t conscious of the connections as todays, yesterdays and tomorrow’s catastrophes accumulate. These Still Lifes as a group somehow collapse and distort time.

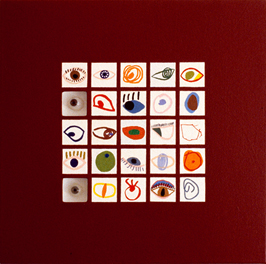

MacPherson’s engagement with catastrophes was stimulated as a student when she came across the residue of a long closed ophthalmic surgeon’s rooms in a second hand shop, trays of glass eyes, mostly it seemed for children. This led to reading about the Halifax explosion of 1917 and a group of paintings Twenty-five eyes / eighty-four years in 2001.

Siné MacPherson

Study forTwenty-five eyes /

eighty-four years 1997

oil on canvas, wood, glass,

and glass eyes

41 x 41 cm

Collection of the artist

MacPherson is attentive to her surroundings, extremely observant of everyday life, always aware that any chance encounter, whether reading or looking, could reveal a small fissure that when explored more fully might become the compositional framework for a painting. The Still Lifes, begun in 2010, are just that, something of commonplace familiarity seen anew. At the time newspaper articles about the practice of commemorating victims from car crashes with shrines led to commentary about the need to clear the roadsides. The shrines were considered a distraction, perhaps even a road hazard. So another part of the fabric of any drive whether across a city or through the countryside seemed under threat? This news came to the artist’s attention about the same time as she was casting about for a motif that would allow her to begin what she felt was a long overdue pleasure, perhaps even an indulgence, painting a series of floral still lifes. In keeping with her usual strategy, the floral arrangements she was chasing had to not be of her own making. After all, what’s the point; it is all out there already, really.

The series began with a road trip to Albany. In fact all of the Still Lifes come from that one trip. That done, the raw data for the entire series, was to hand, pre-determined compositions for an extended group of flower paintings. The key as always was to not overplay the origins of these unique arrangements of flowers for either their psychological or associative references. Roadside shrines are after all reasonably well known, so no need to be sensational, no need to reveal overly personal details, no need for GPS or highway coordinates, and nothing needs to be overstated. The trauma of a car crash warranted an accurate record but more importantly it required recalibration. Recalibrating something commonplace, something found everywhere, every day is what MacPherson has undertaken in all of her work, something Bruce James identified in his review of Twenty-five eyes / eighty-four years, with the “danger of looking” closely.3

A certain danger lurks everywhere; one of the pleasures of any floral arrangement is thinking about what might be being celebrated, a birthday, a life, a friendship? But these Still Lifes aren’t floral arrangements they are paintings, paintings with the elevated emotional tone of detachment. Viewers are drawn by a riotous array of colour and form delineated with a cool head and a calm hand. No emotional bravado is to be found here. But human nature being what it is we seem to want more from every image we encounter and when you scratch the surface of these pictures truncated phrases leap out, “only 15,” “mates forever,” “Norma,” each with the capacity to collapse the pleasure of looking into an anthology of trauma. Equally each painting seems to announce, loudly, “be careful what you look for?” Everything is simultaneously surface and substance, beauty giving way to peril. This is the strategy at the core of MacPherson’s oeuvre, ever attentive to the form, colour, appearance and structure in those ordinary things around us.

Sine MacPherson Anji 2009 photograph

Commonplace catastrophes routinely draw people out of obscurity, and bestow local notoriety and a brief moment in the spotlight on someone. Each of MacPherson’s Still Lifes is a profusion of flowers, a momento mori of just one instant. The taxonomies of materials at each site are mostly similar, numerous flowers in a profusion of colours, a white cross sometimes as many as five, each decorated and often carrying some sort of annotation. In addition there is always debris left by visitors, automotive parts – bumpers, tail light covers and the accumulated residue of one or perhaps many commemorative events– packages, a favourite teddy bear, mementos and bottles. In MacPherson’s paintings things are not quite so clear; the Still Lifes are not simple allegories, not so much about a message sent as how she matches the density of her subject with an almost overwhelming intensity of paint. MacPherson scrupulously reveals the sheen and surface of every colour and object, intent on cataloguing the external characteristics of the visually apprehensible forms and colours from her visit to each site.

Siné MacPherson

Anji 2015

oil on canvas, triptych

59 x 140cm overall

Collection of the artist

The imagery distributed across the surface of the group of Still Lifes avoids direct expression; preferring instead an oblique angle on the already too harsh reality of their subjects. Everything about MacPherson’s painting of these roadside shrines is dignified, formal even; the clarity of her images keeps every option active. These shrines must have been magnificent once, but those were in better days, long past, mostly forgotten. Plastic like memories fade, paint peels creating the tension between appearance and representation. Each layer of complexity unfolds in Still Lifes that take risks, play roles, all the while ensuring that nothing in any of this is really clear. Look closely, listen to your thoughts, and quell your emotions to wonder about the already made in the world around you, every day, everywhere.

Gary Dufour June 2016

1. Ellsworth Kelly. "Notes of 1969." in Ellsworth Kelly, 30-34. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum 1980.

2. One and three chair collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchase 1970.

3. Bruce James. “Review: Twenty-five eyes / eighty-four years .” ABC Radio National, 15 April 2001.